Indiana’s ambitious billion-dollar plan to supply water to Boone County’s LEAP district, a region with limited water resources, has sparked intense debate and controversy. Citizens Energy’s proposal to ship up to 25 million gallons of water daily from Central Indiana’s watersheds, including Eagle Creek, to Lebanon, has drawn significant opposition. The plan involves sending treated wastewater back to Eagle Creek, a move that has raised serious environmental concerns.

Hundreds of Hoosiers have voiced their opposition, attending public meetings and protesting construction sites. The core issue revolves around the potential ecological impact of discharging treated wastewater into Eagle Creek. Martin Risch, a retired hydrologist with extensive experience at the Indiana Department of Environmental Management (IDEM) and the United States Geological Survey (USGS), highlights the complexities involved. “Treated wastewater has things in it that aren’t traditionally measured, and we know these things can accumulate in an ecosystem,” Risch said. “If we ignore those complexities and think it’s as simple a solution of water up and treated wastewater back, we’re overlooking the things that can happen in the ecosystem… and that change could be profound.”

In response to these concerns, Lebanon Utilities announced plans to upgrade its wastewater treatment plant. However, this has done little to assuage the fears of Eagle Creek advocates, who question how the utility can adequately upgrade the plant without pollution permits. The uncertainty surrounding the types of contaminants that might enter the water, given the LEAP district’s largely unpopulated status, adds to the skepticism. Larry Kane, a retired environmental attorney who once worked at IDEM and opposes the plan, noted that while jumbled permit timelines are not uncommon, they are not wise.

The project’s progress has been uneven. IDEM issued a construction permit for the wastewater treatment plant upgrade, but the second phase, which includes the construction of 16 miles of 48-inch pipes running to Indianapolis and a discharge site on Eagle Creek’s north shore, is still navigating a complex permitting process. The utility hopes to receive the construction permit by October 2026, but public interest in the project may delay this timeline.

Environmentalists have expressed concerns about the new plant’s ability to treat wastewater effectively without knowing the pollution limits. Ed Basquill, Lebanon Utilities general manager, assured that the utility has worked closely with companies like Eli Lilly and Meta, which have committed to building in the LEAP district, to design the treatment plant according to their water needs. However, the potential for hundreds of future tenants in the tech park raises questions about the types of contaminants that might enter the water.

As a precaution, Basquill stated that the utility will require companies to test their wastewater and pre-treat it on-site if necessary before sending it to the Lebanon wastewater treatment plant. Despite these measures, members of the Eagle Creek Park Advisory Committee seek more information about the project’s environmental impact. The Indiana Family of Advisors (IFA) determined that Lebanon Utilities’ leg of the project did not necessitate an environmental impact statement, a decision that has baffled many on the committee.

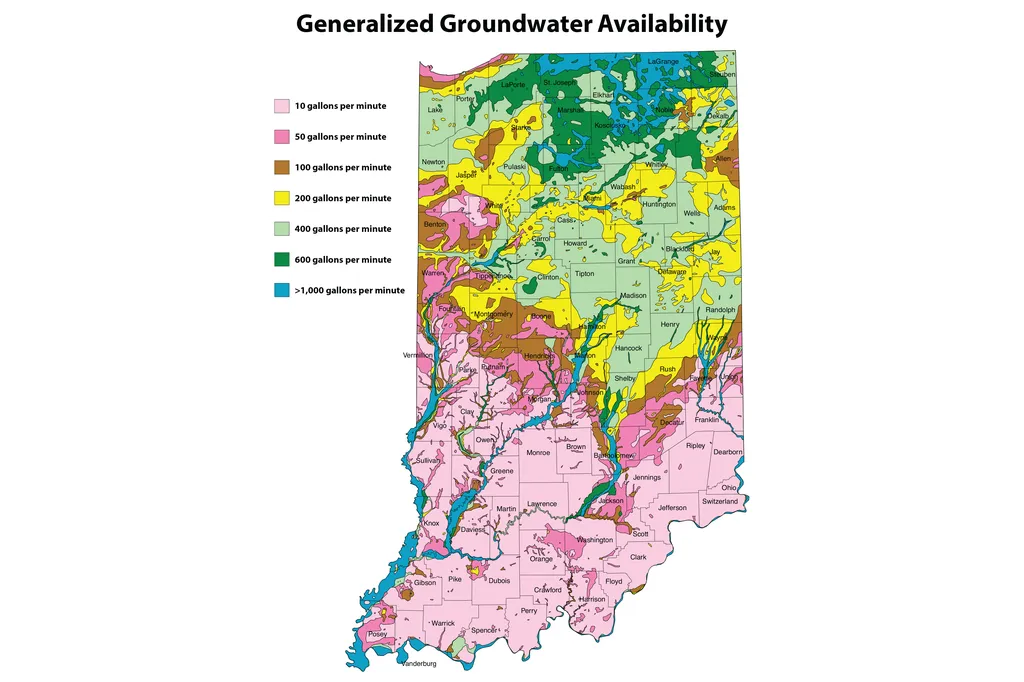

Discharging treated wastewater into a contained reservoir like Eagle Creek is unusual in Indiana, according to Risch. Typically, wastewater is discharged into flowing water, which provides a natural buffer. The lack of accessible and reliable information has made dialogue with the utilities more difficult, according to Lou Ann Baker, a member of the park foundation’s advisory committee. The committee would like to see a water budget to ensure there is enough water to handle the project.

Risch is collaborating with the USGS to conduct a bathymetric study of Eagle Creek, which could provide a more accurate estimate of the reservoir’s capacity. He is also considering the impact of pollutants that IDEM does not monitor. “We are quite aware that not everything that comes out of that pipe at the end of wastewater treatment is measured,” Risch said. “I fear the health consequences that could be associated with this for the creatures that can’t escape.”

This controversy highlights the need for a more transparent and inclusive approach to water management projects. The sector must prioritize thorough environmental impact assessments and engage with the public to address concerns and build trust. The outcome of this debate could shape future water management practices in Indiana, setting a precedent for balancing economic development with environmental stewardship.