In a world where companies are under increasing pressure to account for their environmental impacts, a new approach is emerging that could revolutionize how businesses assess and manage their supply chains. The “supply-shed” approach, as detailed in a recent study published in *Environmental Research Communications* (translated from Japanese as *Environmental Research Communications*), offers a pragmatic solution to the challenges of supplier-level traceability, particularly in the energy sector and beyond.

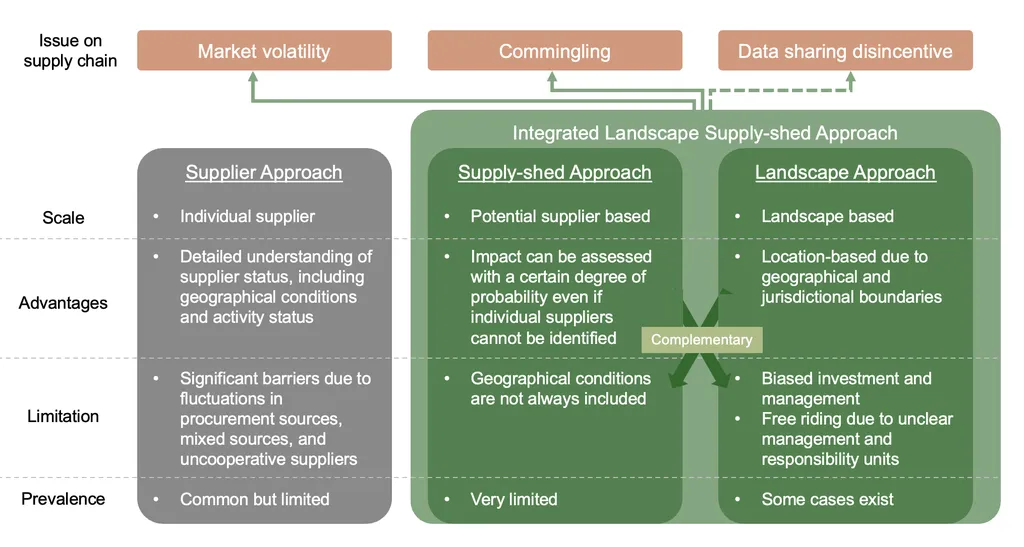

The research, led by Keishi Nakao from the Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences at The University of Tokyo, addresses the significant hurdles companies face when trying to evaluate their environmental footprints across entire value chains. “Supplier volatility, commodity mixing, and nondisclosure by upstream actors make site-specific monitoring highly burdensome,” Nakao explains. This complexity hinders compliance with emerging frameworks like the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), the European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), and the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

The supply-shed approach simplifies this process by grouping suppliers within defined markets or regions, enabling collective impact assessment without the need for precise supplier identification. This method has already been successfully applied in corporate Scope 3 greenhouse gas accounting, reducing costs while maintaining meaningful links to environmental outcomes.

But the innovation doesn’t stop there. By integrating the supply-shed concept with landscape approaches, the study proposes a hybrid framework that balances practicality and ecological relevance. “The supply-shed brings organizational clarity and accountability within supply chains, while the landscape approach anchors assessments in spatial and ecosystem-specific boundaries,” Nakao notes. This integration allows companies to conduct initial risk screening at regional scales using secondary data, remote sensing, or environmental DNA (eDNA), followed by targeted supplier-level studies when higher resolution is necessary.

For the energy sector, this could mean more efficient and cost-effective ways to monitor and manage environmental impacts across complex supply chains. The hybrid approach offers a systematic way to address traceability barriers, supporting more credible contributions to global biodiversity conservation.

However, challenges remain. Defining responsibility across overlapping supply-sheds and ensuring coordination within broader landscapes are critical issues that need to be addressed. Aligning with regulatory regimes that may burden smallholders is another concern. Despite these challenges, the study suggests that embedding supply-shed–landscape hybrids into evolving policy frameworks presents a cost-effective and inclusive pathway for corporate natural capital assessment.

As the energy sector continues to grapple with the need for sustainable practices, this research offers a promising avenue for progress. By lowering financial and technical barriers, expanding corporate participation, and fostering more credible contributions to global biodiversity conservation, the supply-shed approach could shape the future of environmental impact assessment and management.

In the words of Nakao, “This model offers efficiency in addressing traceability barriers and supports more systematic monitoring of biodiversity, water, and land-use impacts.” As companies strive to meet increasingly stringent environmental regulations, the supply-shed approach may well become a cornerstone of sustainable supply chain management.