The water sector is on the cusp of a digital revolution, one that could redefine how industries manage one of our most precious resources. Ashok Kumar Kalyanam’s work shines a light on the stark reality of industrial water use: a significant portion of freshwater is unaccounted for, and outdated monitoring systems are failing to keep up. His research offers a roadmap for change, one that could reshape the sector’s approach to water management.

Industrial plants are the world’s thirstiest entities, guzzling 20% of global freshwater. Yet, most plants can’t track a third of their water usage. This isn’t just an operational oversight; it’s a crisis in the making. With 25 countries already using over 80% of their available water, every lost liter is a step closer to scarcity. The current system is a patchwork of manual readings, delayed reports, and reactive maintenance. It’s a system primed for failure, and it’s holding the sector back.

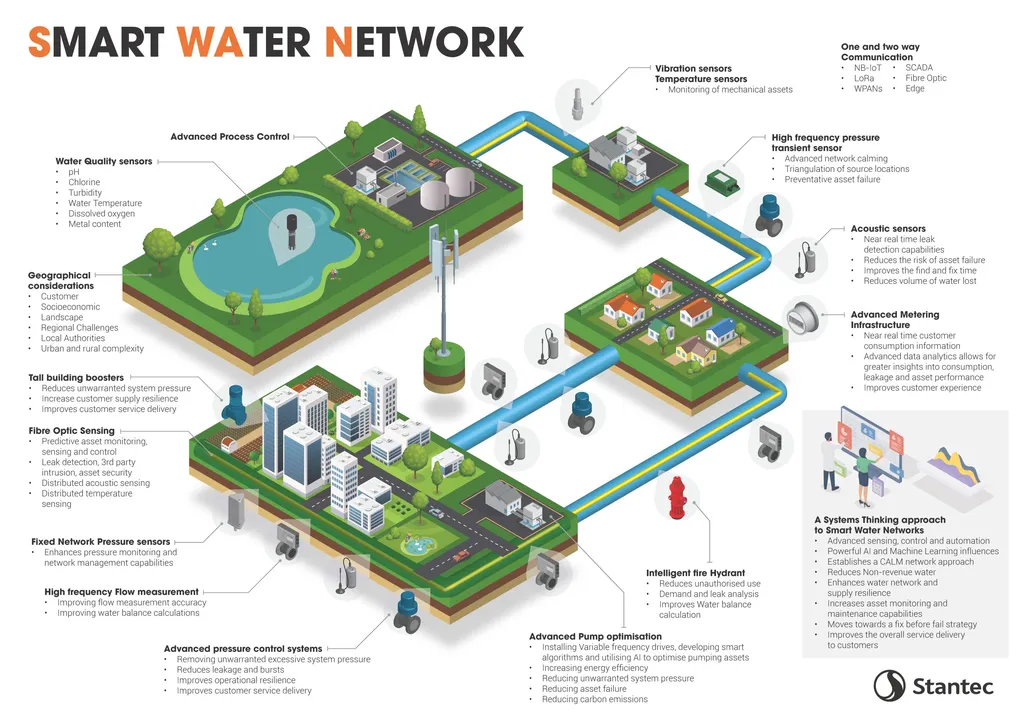

Kalyanam’s solution is a digital overhaul. By replacing manual monitoring with sensor networks and analytics software, plants can track water usage in real-time, predict failures before they happen, and optimize water use. His framework is a three-part system: sensors that monitor flow, pressure, and chemical levels; a middle layer that sorts and filters data; and software that learns normal patterns and alerts engineers to anomalies. This isn’t just about collecting data; it’s about connecting data streams to create a comprehensive picture of water use.

The benefits are clear. Plants using this system have seen efficiency gains of 35-50%, cost savings ranging from hundreds of thousands to millions per year, and quicker regulatory compliance. But the transition isn’t seamless. High costs, interoperability issues, data security concerns, and skills gaps are significant hurdles. Kalyanam’s framework addresses these challenges, advocating for a phased approach that minimizes risk and allows staff to adapt.

The influence of Kalyanam’s work extends beyond the case studies. It’s shaping research, education, and industry practices. Engineering schools use his case studies to teach resource optimization. Water departments use his framework to evaluate vendor pitches. Equipment makers are incorporating his interoperability standards into their development plans. His work is a testament to the power of evidence-based practice.

Looking ahead, the potential for innovation is immense. Edge computing, AI-driven treatment processes, and blockchain for water rights are just a few areas ripe for exploration. The chip industry’s experiments with closed-loop recycling could cut freshwater needs by 60%, a game-changer in water-scarce regions.

The water sector stands at a crossroads. Climate change, population growth, and regulatory pressures are tightening the screws on water use. Companies that invest in smart water management now will be better equipped to handle these challenges. Kalyanam’s work provides a template for this transition: document what works, identify failure points, publish replicable methods, and update the framework as technology improves.

This isn’t just about adopting new technology; it’s about rethinking how we manage water. It’s about shifting from reactive to proactive, from delayed to real-time, from fragmented to comprehensive. The digital revolution is here, and it’s time for the water sector to embrace it. The question isn’t whether smart water management will become standard; the economics and resource pressures point that direction. The question is how fast industries can deploy before external forces make the transition more urgent and expensive. The time to act is now.